Those of us working in the field of health are now used to the statistic that health care contributes 4-5% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Surely it is right therefore that the whole health care sector take responsibility for this and contribute to the COP21 Paris agreement to reach global net zero by 2050?

There has been a flurry of activity in recent years and months as more and more researchers in the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) community scramble to consider what we should be doing to contribute to the global effort. I’m here to argue that we should not being doing much at all. Indeed, that by and large, in the land of HTA and health economic evaluation, it should be business as usual.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that we should ignore the threat of climate change, rather that the problem is beyond the narrow perspective of HTA and that we should factor this into our considerations. Decision making at the HTA level is simply too late in the day to have the important impact required if we are to address the urgent challenge presented by the climate crisis.

Let’s start at the beginning, which for the economist is Arthur Cecil Pigou. It was Pigou that introduced the concept of externalities into modern economics (building on the work of his mentor Alfred Marshall). Pigou argued that the social costs of industrial activity are not borne by the polluter and so industrial activity is higher than is socially optimal. Pigou’s classic example was a smoky factory whose pollution reduced crop yields, soiled laundry, caused health issues for local residents and reduced local property values. Given what we know about the climate crisis, the local aspects of Pigou’s example seem rather quaint. GHG emissions have a reach much further than Pigou imagined causing rising temperatures, extreme weather events, biodiversity loss, increased disease and rising sea levels—all on a global scale. But these costs are not borne by the emitter nor priced into goods or services. This results in a market failure with overproduction of activity generating GHG emissions and underinvestment in cleaner/greener alternatives.

It seems clear that the current climate crisis is a textbook example of a negative externality and there is of course a textbook solution to this problem—the so-called Pigouvian tax. The idea is that Governments should impose a tax on polluters to correct the market failure such that the private cost to the polluter aligns to the full social cost. This curbs demand for the polluting activity back to levels that are socially optimal.

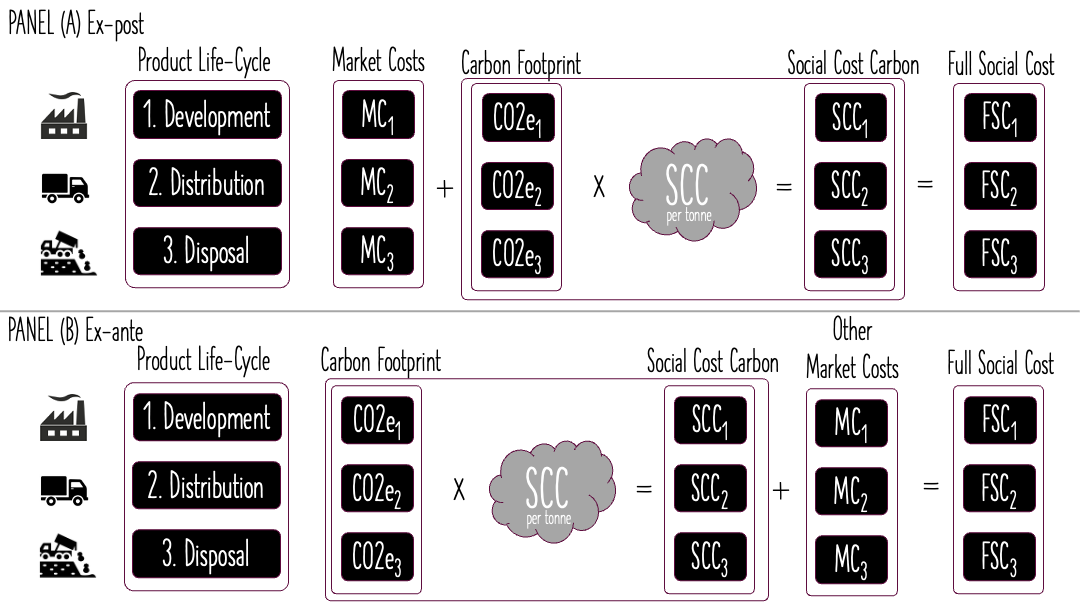

How does all this relate to HTA and health economic evaluation? Well it depends on how the externality is to be internalised. Should we internalise the externality at source (ex ante) or undertake a carbon footprint accounting exercise after the fact—using life cycle analysis (LCA) methods—and internalise the externality ex post?

These two solutions are illustrated in the figure above. Production of a (health technology) good is characterised into three stages across its lifecyle: development, distribution and disposal. The upper panel (A) of the figure shows the ex post solution. A carbon footprint analysis is undertaken to establish carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions after the fact and market prices are updated to full social costs using the social cost of carbon (SCC). The lower panel (B) shows the same procedure but assumes the carbon foot-printing and imposition of the social prices occurs further upstream in the process. Economists are fond of their ceteris paribus (all else equal) assumption and on the face of it, the illustration in the figure seems to suggest that ex ante or ex post we arrive at the same place. But in practice, the difference between the two approaches is that manufacturers of health technologies will be incentivised through the market to adapt to cleaner/greener production if they face the full social costs at all stages of the lifecycle. Further, if that happens, then there is no need to adapt our HTA methods since we can be confident that the negative externalities are already internalised and therefore reflected in the price of the health technology.

It should be clear from the example above, that compared to an ex ante internalisation of the externality, an ex post internalisation at the stage of HTA decision making is hugely inefficient. But there is another, and more compelling, reason why we should avoid the trap of thinking we should be obliged to ‘green’ our HTA methods. That is that climate change is a global phenomenon impacting all sectors of the economy not just the health sector. It’s hugely inefficient to apply ex post methods of capturing GHG emissions only in the health sector, if other sectors are not playing ball. We need a level playing field, and the field will be levelled by imposing upstream taxes on those contributing to GHG emissions.

Let’s return to the idea that health care, as a sector, contributes 4-5% of global GHG emissions. Now let’s choose another sector—the aviation industry—which contributes around 2.5% to global GHG emissions. On the face of it, based on contribution to GHG emissions, we should worry less about the aviation industry than the health care industry. But this misses a number a hugely important points about the aviation industry.

First, passenger numbers are expected to increase 2.5 times from around 10 billion in 2024 to nearly 25 billion in 2052 (around the same year of the Paris agreement targets). Second, nearly 50% of all passengers are flying internationally rather than domestically. Why is this important? Because international air travel is exempted from the national GHG emission targets agreed by the council of the parties (COP). Finally, and perhaps most devastatingly, who are these people who are flying? Well, it has been estimated that 90% of the world’s population does not fly, so you can guess who the guilty 10% are. Airline travel is the privilege of rich people in rich nations. There is a fundamental inequity involved in this sector of the economy that is simply not as pronounced (we cannot claim it does not exist) in the health care sector.

To be frank, it would be perverse if the use of ‘green HTA’ methods means that the health care sector bears a greater responsibility for reducing GHG emissions than the aviation sector—yet that is the path we are on. The solution is ex ante taxes on GHG emissions that level the playing field across all sectors.

Okay, I’ve argued that the ideal solution is to have the negative externalities of climate change internalised into market prices and then let the market do its thing. This would mean that we don’t have to change our HTA methods because we could be confident that health technology prices incorporate penalties for the environmental harms they produce. But this ideal solution does not exist, so shouldn’t we be doing something to help in the HTA community? Isn’t doing something better than doing nothing?

Many readers will be familiar with the classification of GHG emissions into three scopes by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol—a framework established to provide a standardised method for organisations to measure and manage their GHG emissions across various operational boundaries. Scope 1 emissions are those under the direct control of the organisation, scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from power supplied to the organisation and scope 3 emissions are all other indirect emissions from upstream and downstream partners in the supply chain. Crucially, third scope emissions of one organisation should be scope 1 emissions of another organisation.

I wonder whether having three scopes for handling environmental impacts in HTA might be the way to go? To be clear, this would not be the same three scopes of GHG emissions, simply the idea that we can prioritise when we need to consider environmental harms and when they might be safely left to one side. Scope 1 in a green HTA might be reserved for technologies that themselves have a direct damaging effect on the environment. Examples might be anaesthetic gases (which can have a much more damaging effect than CO2 but which can be captured by considering their CO2e), inhalers containing environmentally damaging chlorofluorocarbons versus dry powder inhalers, or disposable versus reusable medical equipment. By contrast, Scope 3 HTA might omit environmental considerations if technologies being compared have no a priori reason for being more or less environmentally damaging than each other. This might be the case for oral products for the treatment of the same condition, for example. Scope 2 would be somewhere in the middle—where the technologies under evaluation do not directly cause environmental damage, but where the process of care is sufficiently different that an a priori differential contribution to GHG emissions might be apparent.

But even here we should exercise caution. A fundamental theory of welfare economics is the general theory of second best which contends that when the first-best conditions necessary for achieving optimal outcomes cannot be met (in our case a concern that other sectors are not achieving appropriate GHG reductions) then pursuit of the remaining conditions (in our case internalising the negative externality in the health sector through greening HTA) does not necessarily lead to efficiency. This counterintuitive result suggests that policy interventions must consider the interplay of various market imperfections rather than addressing them in isolation and should give us, in the HTA community, pause before suggesting wholesale changes to our approach that impacts only the health care sector.

In closing, and in recognition of the fast moving evolution of proposed solutions to the climate crisis in our field, I want to reflect on those developments that I think are helpful generally and contrast them with those that I find generally unhelpful. The danger is, that scarce evaluative resources are squandered in the pursuit of expanding methods and approaches that are not fit for purpose and are likely to make decision making and the HTA process less efficient.

In the helpful generally category, I would put the recent efforts to update the SCC—there is now good evidence that $51 per metric tonne of CO2e is woefully inadequate. Further work might even consider whether the potential losses in GDP from catastrophic climate change should also be incorporated? Also, we should be reviewing discount rates to make sure that we don’t undervalue the benefits to future populations. Distributional analyses should explore not just the burden of climate change geographically, but also inter-generationally. There is a concern that an intersectionality argument applies whereby the burden of climate change will be felt by the poor, in poor nations, and in the next generation. Poverty and displacement caused by climate change can increase political instability increasing the chance of conflict. Finally, I wonder if a simple reframing exercise of presenting the SCC in terms of health benefits forgone, rather than as a dollar cost, could help a skeptical audience to better understand the consequences of climate inaction.

In the generally unhelpful category, I would put a whole bunch of recent proposals for how to green HTA methods. Taking life-cycle methods and proposing they become a routine part of an HTA would create a huge burden on HTA analysts (but would be good for LCA consultants!) Similarly, the idea that conducting multi-criteria decision analysis with health care decision makers or the public, or even to pass the burden of green HTA to a committee in a deliberative process, is to miss the point of needing a inter-sectoral solution to the problem, not a health care solution. Finally, the idea that decision making will somehow be improved by conducting a carbon footprint analysis and then presenting decision makers not only with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) but also an incremental carbon footprint effectiveness ratio (ICFER) and an incremental carbon footprint cost ratio (ICFCR) is almost laughable. What are decision makers supposed to do with this information? What are the decision rules that will lead to optimal outcomes?

It is important that we all engage with the challenge that is presented by human contribution to climate change on our planet. This is perhaps the greatest challenge of our generation, and one on which our actions will surely be judged by future generations. But as a health economics and HTA community I would caution humility. Our desire to do something to help, however well intentioned, should not lead us down a path of knee-jerk changes to our methods. There is a real danger of overreach—that in attempting to correct unilaterally for a global problem we actually make the situation worse. Do we really want to sacrifice population health outcomes so that the rich can continue to enjoy cheap international travel?

Or you can generate insights as part of the HTA that are useful and drive change